Anthea Paelo and Pamela Mondliwa

Kenya’s recent competition case against DSTV in the pay-tv industry is only one more in a growing list of complaints relating to exclusive agreements in the industry in African countries. In this particular case, Zuku, a satellite pay-tv provider and competitor to DSTV,1 approached the Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) to protest MultiChoice’s (DSTV’s parent company) exclusive rights over content such as broadcasting of the English Premier League (EPL).2 The complainant alleges that this conduct amounts to a restrictive trade practice in violation of Kenya’s Competition Act, Part III of Section A.3 Sporting events and particularly broadcasting live games draws a lot of consumers and is considered “must have” content for premium pay-tv packages and in some jurisdictions it has been regarded as an essential facility.4An essential facility can be defined as an “infrastructure or resource that cannot reasonably be duplicated, and without access to which competitors cannot reasonably provide goods or services to their customers”.5 Zuku argues that SuperSport (a subsidiary of MultiChoice) which owns the broadcasting rights for the EPL sells its exclusive content only to DSTV, a vertically integrated retail distributor.

Similar cases have emerged in South Africa and Botswana with cases being brought against MultiChoice. There has also been a case relating to tying and bundling and exclusive content in Egypt where the Egyptian Competition Authority determined that obligating viewers interested in watching world cup football matches to subscribe for a year was abuse of dominance.6 The case in South Africa also concerns MultiChoice’s exclusive rights to SuperSports’ content. Sports programming is well known for drawing in a number of subscribers especially when broadcasting major sports events such as the world cup. MultiChoice in South Africa is said to have so much exclusive sports content that it is in “excess of what is offered by Sky Sports in the UK”7, a firm that faced similar charges in Europe.8 Two complaints were lodged with South Africa’s Competition Commission regarding the monopoly MultiChoice’s subsidiary SuperSport holds over premium sports content like the Premier Soccer League (PSL), the EPL, Springbok Rugby games and Super Rugby matches, cricket and the local sports tournaments.9 The complainants allege that MultiChoice’s refusal to give downstream competitors access to their exclusive sports content is anti-competitive. Botswana’s competition authority is investigating DSTV’s channel bouquet bundling and pricing structure to determine whether the pay-tv operator’s dominance enabled it to price its material excessively.10

Evolution and structure of the pay-tv market

The pay-tv market evolved from the US cable-tv system in which everyone had access to Free to Air (FTA) channels provided by a national broadcaster. Profits were earned from advertising and public subsidies. However new transmission technology emerged that allowed conditional access to valuable content by means of an encryption code for a subscription fee.11 Thus in order to attract more paying consumers, pay-tv operators had to acquire exclusive content not already provided on FTA channels. Following this, consumers only had access to premium content such as recent movies and major sports events if they subscribed to a particular pay-tv operator. To increase the value of their premium content, production companies began issuing licences and pay-tv operators were willing to pay very high prices for the exclusive rights to transmit this content ‘live’ in the case of sports events or in the first window period for movies.

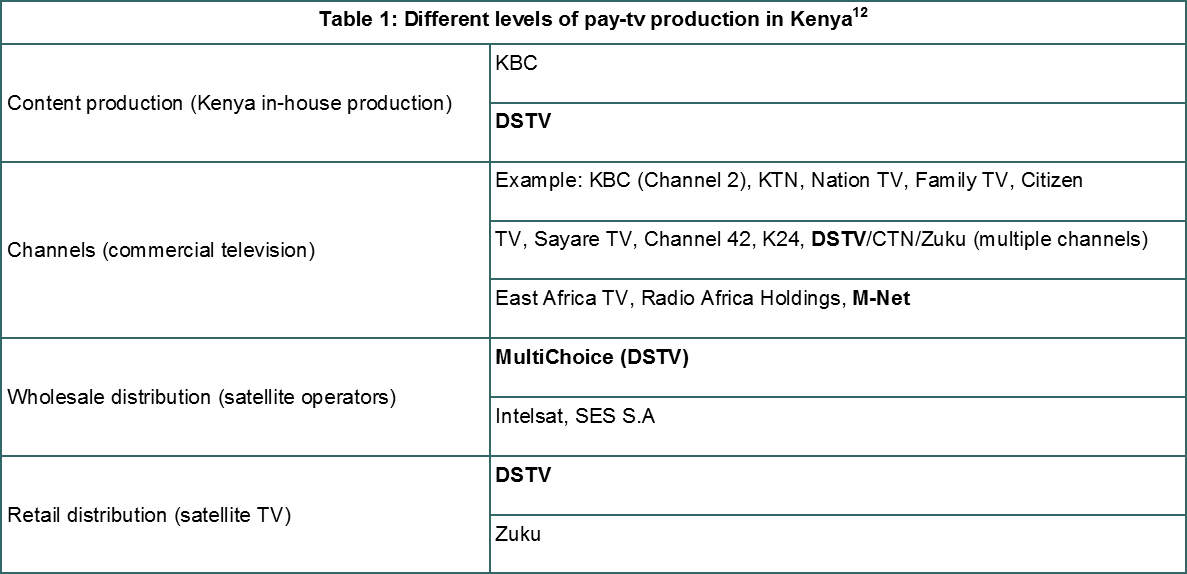

New technology and the changing structure of the pay-tv market has now allowed for vertical integration along the value chain which allows the monopoly (the rights holder) to leverage its position further down the value chain. There are four main levels along the supply chain; production of content, acquisition and ‘assemblage’ of content into channels, programming of channels into bundles to be sold to subscribers, and transmission via technological platform.13 Vertical integration across all four levels of the supply chain can raise anti-competitive concerns. This is because the firm has the incentive to increase profits by foreclosing its downstream competitors in retail distribution through denying access to must have content. DSTV in Kenya is present at every level of the pay-tv industry (Table 1).

Anti-competitive effects of exclusive rights in pay-tv

The Kenyan Act does not set the legal and economic tests for a restrictive trade practice assessment and the appropriate criteria for evaluating exclusive agreement cases may vary from one jurisdiction to the other. Competition authorities often deal with exclusive agreements in one of two ways; as an abuse of dominance where one of the contracting parties must be shown to have market power, or as an anti-competitive agreement. Exclusive agreements are not necessarily anti-competitive and thus an authority evaluating these cases will have to identify a theory of harm supported by strong evidence whereby the arrangement results in substantial foreclosure which has harmed competition – an effects-based test. An assessment of exclusive agreements will generally include; establishing that there is an exclusive agreement, the definition of the relevant market and the suppliers within that market, the extent of competitive effects from the arrangement and balancing this with possible pro-competitive justifications for the agreement.14 Establishing whether the conduct has anti-competitive effects will be the most challenging step of the analysis but there is guidance from case precedence.15 The analysis may include a determination of the coverage of the conduct in the relevant market, the duration of the agreements, existence of alternative sources of supply, scale economies, ease of entry and market dynamics, evidence of competitive effects such as increased prices or exit of firms and the potential efficiencies.16

Exclusive rights in pay-tv markets act as a barrier to entry by raising competitors’ costs and deterring or delaying entry into the market.17 As the holder of the rights stands to gain more profits by increasing the number of potential viewers, pay-tv operators have to pay higher prices for the exclusivity of the premium content to make up for the reduced profits the rights holder gets by selling to only one pay-tv operator. In Europe, authorities have recognized this as the pay-tv incumbents’ strategy to foreclose rivals by raising their costs and deterring entry.18 It also has the added disadvantage of raising prices for consumers. For instance, in Kenya, MultiChoice’s premium content allows it to charge almost twice as much as for its Compact bundle compared to Zuku its closest competitor.19

Furthermore, because, the industry is characterised by network effects, the incumbent pay-tv operator enjoys the positive externalities of having grown a large customer base. The customer base enables the operator to continue to pay for the highly priced exclusive premium content and has the added benefit of locking in customers due to high switching costs. These switching costs mostly arise due to technology. In order to switch from one operator to the other, installation of hardware such as satellite dishes and decoders for the particular operator has to take place and the cost is incurred by the consumer.

There are arguments in favour of exclusive agreements on efficiency grounds. Exclusive agreements and vertical arrangements reduce the transaction costs generated by asymmetric information, prevent free-riding, and protect intellectual property and brand-name however these factors need to be carefully balanced against the risk of anti-competitive outcomes. 20 The remedies typically applied from international cases21 include placing a ban on exclusive rights arrangements or exclusive vertical contracts, limiting the scope and duration of exclusive rights arrangements, having the competition authorities direct the nature and process of establishing exclusive rights arrangements, wholesaling exclusive premium content or retailing channels created from wholesaled exclusive content.22 Short exclusive contracts and wholesale of premium content or the retail of channels with exclusive content are most likely to increase competition. Completely banning the exclusive vertical arrangements on the other hand could severely impede the operation of the market by undermining the incentive to invest in producing and purchasing content.23

Conclusion

There is a notable shift in the treatment of exclusive content agreements in pay-tv markets by competition authorities towards a view that access to content is imperative for entrants to be able to compete with incumbents. In Europe, rights sharing remedies have been applied and conditions have been placed on the duration and scope of exclusivity. In some cases, exclusivity has been banned altogether. This would encourage competition based on quality of service, pricing, packaging strategies and technological advances, which have consumer welfare benefits.

In several African jurisdictions there are an increased number of complaints regarding exclusive content agreements as leading to high barriers to entry and raising consumer prices for pay-tv content. Where these agreements are of a longer duration or a broad scope and the market is highly concentrated, the likelihood of anti-competitive harm is generally greater. However, a number of these cases, including in Kenya and South Africa, have yet to be concluded. In evaluating these complaints, it is critical for authorities to balance any findings of anti-competitive effects against the efficiency justifications that will typically be put forward by respondents, including whether those efficiency gains will be passed-through to consumers.

Please click here for a pdf version of the article.

Notes

- Deloitte. Competition study – the broadcasting industry in Kenya. Dissemination Workshop (March 2012).

- Mbole, K. ‘Zuku to take CCK to court over DSTV monopoly on content’ (19 March 2013). Humanipo.

- Kenya Competition Act No. 12 of 2010.

- See, for example, European Commission, Newscorp/Telepiu merger, Case No. COMP/M.2876.

- South African Competition Act No. 89 of 1998.

- African Competition Forum. (2014). ‘ECA on violation to Competition Law concerning World Cup Matches Broadcasting’. African Competition Forum Newsletter.

- Mochiko, T. ‘MultiChoice’s pay-TV dominance in the spotlight’ (4 June 2013). Business Day.

- See, for example, ‘Decision under section 3(3) of the Broadcasting Act 1990 and section 3(3) of the Broadcasting Act 1996: Licenses held by British Sky Broadcasting Limited’.

- Gedye, L. ‘DStv’s grip on sports under scrutiny’ (2 June 2013). City Press.

- Benza, B. ‘Competition Authority probes MultiChoice’ (22 October 2014). Mmegionline.

- Nicita, A. & Ramello, G. B. (2005). ‘Exclusivity and Antitrust in media markets: The Case of Pay-TV in Europe’ in International Journal of the Economics of Business, 12(3):371-387.

- See note 11.

- See note 11.

- International Competition Network (ICN). Chapter 5: ICN Unilateral Conduct Workbook.

- See, for example, European Commission in Newscorp/Telepiu, Case No. COMP/M.2876; and note 8.

- See note 14.

- See note 11.

- See note 11.

- See note 1.

- See note 11; de Fontenay, C. & Gans, J. (2004). ‘Can vertical integration by a monopsonist harm consumer welfare?’ International Journal of Industrial Organization, 22(6): 821–834; and Ratshisusu, H. (2010). ‘Preconditions of a Competitive Pay-TV Market: The Case of South Africa’. Presented at the Annual Competition Commission Conference 2010.

- See note 11.

- Paterson, P., Sethi, P. & Saadat, U. ‘Content Access: The New Bottleneck?’ Communications Policy & Research Forum 2011, Sydney.

- See note 22.