Anthea Paelo

As of 2014, about two-thirds of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa were financially excluded. 1 Financial inclusion, defined as access to financial services such as savings and credit, is important for any economy that intends to achieve inclusive growth and development. Good financial systems are necessary to provide access to saving, credit and risk management to help the poor start and expand businesses, absorb financial shocks and invest in education. 2 Constraints to greater financial inclusion include a lack of money to use an account, the high cost of accounts, long travel distances to financial institutions, lack of required documentation, onerous bank regulation and poor road infrastructure. 3 There is also a lack of credit information regarding the unbanked. Before a financial intermediary can lend money they must be able to determine how much can be lent, for how long and at what cost. In order to have this kind of information, however, the financial intermediary must have access to an applicant’s credit record which in the case of the unbanked is often non-existent.

Mobile money technology, capitalising on the high levels of mobile phone penetration in sub-Saharan Africa, has created a means of overcoming some of these barriers. The term mobile money is used to refer to a number of distinct but related services offered over a mobile digital platform including; mobile money transfer, mobile payment and mobile banking. Mobile money transfer (MMT) is the basic transfer of mobile money between two mobile money subscribers over a mobile network. 4 This is the most common use of mobile money in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mobile payment refers to the transfer of mobile money for the purchase of goods or services, usually used for paying utilities such as electricity and water, school fees and merchants. 5 Mobile banking, on the other hand, is the use of mobile devices to access banking services such as deposits, withdrawals, loans, savings, account transfers, bill payments and inquiries. For a subscriber to access these services, they require an account at a bank and these services are usually offered by banks as added value to traditional banking products.

By providing a cheap, more accessible, convenient and safer means for cash transfer, mobile money has proved to be a driver of financial inclusion. 6 Between 2011 and 2014, mobile money accounts contributed to growth from 24% to 34% in accounts held overall including with banks, micro-credit, sav-ings, loan cooperatives and mobile wallets. 7

The evolution of MMT to mobile financial services

The role of financial intermediaries like banks is to reduce the information and transactions costs arising from the information asymmetry between individuals with cash to spare and those that do not have (potential borrowers and lenders). 8 Financial intermediaries develop expertise in collecting information, evaluating and monitoring potential borrowers, lenders and projects to fill the information gap. 9 However the ability for financial intermediaries to perform this role efficiently is dependent on the availability of some kind of record on potential borrowers’ net worth, ability to make repayments and the viability of the project they want to undertake. Where individuals and firms do not have formal deposit accounts through which financial intermediaries can monitor their credit record, it becomes difficult to assess whether the potential borrower qualifies for a loan and for how much.

Mobile money technology helps overcome these information asymmetries by generating credit records from the assessment of mobile money transactions and airtime purchases by subscribers. By partnering with mobile money providers to make use of these credit records, financial intermediaries are better able to evaluate and allocate loans to potential borrowers, providing essential financial services to the formally excluded. When mobile money providers partner with banks and other financial intermediaries to provide these services, including loans, insurance and savings products, it is referred to as mobile financial services. For instance in Kenya, Safaricom formed a partnership with the Commercial Bank of Africa (CBA) in which Safaricom mobile money users can open an M-Shwari bank account via their mobile phone. 10 KYC (know-your-customer) information submitted when opening the M-PESA account is used to open the bank account thus eliminating the need to complete forms or even go to a bank. M-Shwari account holders can gain interest on their savings and even access a micro-credit loan.

However, mobile money has only been successful in a small number of countries. Additionally, in the countries in which it has been successful, the evolution from mobile money transfer to other mobile financial services such as savings and credit has been slow. 11 In Uganda for instance, savings and credit facilities were only introduced in August 2016 although mobile money services were launched as early as 2009. Neighbours Kenya and Tanzania introduced credit and saving services in 2012 and 2014, although mobile money trans-fer services were launched in 2007 and 2008, respectively. 12 In Zambia, the shift to mobile financial services is yet to take place despite mobile money transfer having been launched in 2011.

Competition dynamics in the mobile money sector

A key aspect of increasing access to financial services is affordability. The structure of mobile money markets shapes outcomes and prices may be higher in concentrated markets which limits the ability of people to access these services. CCRED recently conducted a study for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in which it assessed competition dynamics of the mobile money industry in Uganda, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, with interesting comparisons.13

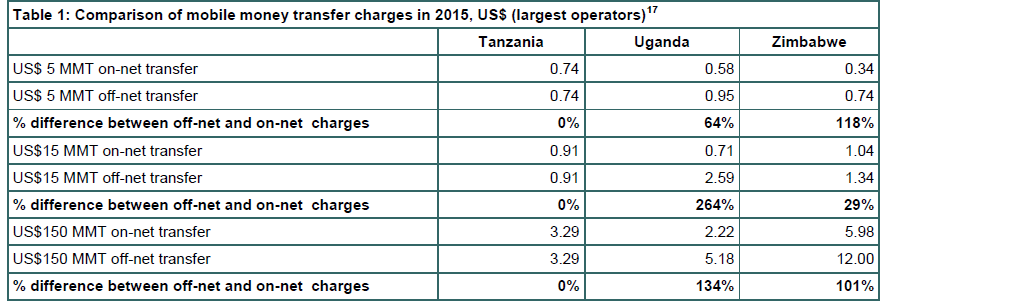

All three countries are largely similar in terms of development. They each have concentrated mobile money markets. Uganda has six mobile money providers although one MNO, MTN Uganda, has an effective market share of more than 70%. 14 . The case is similar in Zimbabwe where there are three mobile money providers but with Econet holding approximately 90% of the market share in terms of mobile money revenues., 15 The situation is a bit different in Tanzania where there are four mobile money providers, two of whom have a market share of 54% (Vodacom) and 40% (Tigo), respectively. 16 The effects of the different structures in the mobile money sectors are apparent when comparing the different mobile money transfer charges, particularly when looking at the difference between on-net and off-net charges.

In Uganda and Zimbabwe where the sector has clear dominant players, off-net charges (transfers across different net-works) are significantly higher than the on-net charges. In Uganda, the charges in the US$15 range are as much as 264% higher than on-net charges (Table 1). In Zimbabwe where the majority of transfers are in the US$ 5 range, off-net charges are 118% more than on-net charges (Table 1). This price differential gives new mobile money subscribers an incentive to join the larger network and subscribers on rival networks to switch so as to benefit from the lower fees as well as access to a larger number of subscribers. On the other hand in Tanzania where there is a more even distribution of the market share, off-net charges are no different from the on-net charges. Although this is partly a function of the interoperability of mobile money providers in Tanzania, it also illustrates the benefits of rivalry in reducing prices and thus accessibility for consumers.

Notes

1. GSMA Intelligence. (2015). ‘The Mobile Economy 2015’. GSMA.

2. Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L. F., Singer, D., and Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). ‘The Global Findex Database 2014: measuring financial inclusion around the world’. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 7255 and Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and Klapper, L. F. (2012). ‘Financial inclusion in Africa: an overview’. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (6088).

3. Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and Klapper, L. F. (2012). ‘Financial inclusion in Africa: an overview’. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (6088).

4. Roberts, S., Macmillan, R., and Lloyd, K. (2016). ‘A Comparative Study of Competition Dynamics in Mobile Money Markets across Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe.’ CCRED unpublished report.

5. See note 4.

6. Macmillan, R. (2016). ‘Digital Financial Services: Regulating for Financial Inclusion. An ICT Perspective’. GDDFI Discussion Paper.

7. Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L. F., Singer, D., and Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). ‘The Global Findex Database 2014: measuring financial inclusion around the world’. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 7255.

8. Claus, I. and Grimes, A. (2003). ‘Asymmetric Information, Financial Intermediation and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism: A Critical Review’. New Zealand Treasury Working Paper No. 03/19.

9. See note 8.

10. Safaricom website.

11. Evans, D. S., and Pirchio, A. (2015). ‘An Empirical Examination of Why Mobile Money Schemes Ignite in Some Developing Countries but Flounder in Most’. Review of Network Economics.

12. Macmillan, R., Paelo, A. and Paremoer, T. ‘The ‘evolution’ of regulation in Uganda’s mobile money sector’. (15 September 2016). The 1st Annual Eastern Africa Competition and Economic Regulation Conference, Nairobi, Kenya.

13. See note 4.

14. Macmillan, R., aelo, A. and aremoer, T. ‘A Comparative Study of Competition Dynamics in Mobile Money Markets across Tanzania, Uganda and Zimba-bwe: Uganda Country Paper’. CCRED unpublished report.

15. Vilakazi, T., Kaziboni, L. and Zengeni, T. (2016). ‘A Comparative Study of Competition Dynamics in Mobile Money Markets across Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe: Zimbabwe Country Paper’. CCRED unpublished report.

16. Robert, S. Blechman, J. and Odhiambo, F. (2016). ‘A Comparative Study of Competition Dynamics in Mobile Money Markets across Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe: Tanzania Country Paper.’ CCRED unpublished report.

17. See note 4 and websites of the largest mobile money operators in Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe.