Digital Industrial Policy Brief 9

John Stuart[1] and Anthony Black[2]

Overview of the Cape Town software development cluster

The Cape Town ICT sector is a globalised and leading services sector within Africa. Many firms in the sector – not just the large multinationals – have international investors, clients, financiers, suppliers and partners. The sector is more than the sum of its parts because it serves as a localised hub of diverse enterprises, a skill pool, financier support, local and provincial government support and a strong physical infrastructure. It is the fastest growing services sector in the Western Cape. Within the broader Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector, business and software services are the highest value-add activities, and the software sub-sector geographically located within the greater Cape Town area is the focus of this brief.

The Cape Town software development cluster (CTSDC) has styled itself on the ‘Silicon Valley’ node near San Francisco. Silicon Valley is host to the technological leaders of today, including Apple, FaceBook and Google. Likewise, the greater Cape Town metro (including Stellenbosch and Somerset West), is home to tech leaders such as Amazon (South Africa), Thawte, Naspers, PayFast and Snapscan. ‘Silicon Cape’ is the name given to the initiative – a hub of ICT firms, collaborative initiatives, funders and governmental partners. The City of Cape Town and the Western Cape Government, together with its non-profit partners, have consciously driven the process of developing the sector to the point that it is a continental and global south leader today.

The CTSDC is part of a growing services sector in South Africa. Services value-added are growing in absolute terms as well as relative terms, partly displacing manufacturing output as a share in total value-added. While the share of the broader ICT sector in total output is around 3%, the contribution of the software sub-sector is much smaller and the sub-sector makes up less than 12% of the overall ICT sector[3]. It is apparent therefore, that the CTSDC is a niche sector within a sector, albeit one that boasts high-skill, high value-added activities and has the potential for rapid growth.

Cape Town is an attractive choice for tech investors and start-ups, for a number of reasons:

A hub of technology companies (or ecosystem) ranging from micro start-ups in the software-as-a-service (SaaS) arena, such as Sudonem, to outsourced sub-divisions of massive multinationals, such as Amazon Web Services.

A large talent pool of diverse skills in the sector, fed into by a number of quality tertiary institutions. These include the University of Cape Town, Stellenbosch University, the University of the Western Cape and the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. There are also several smaller colleges and online learning establishments, which provide short and medium length courses and certifications in the technology sector.

A concentration of venture capital and angel investors focussed on the sector.

A city and local state mechanism that actively encourages the sector.

A network of support services such as fibre connectivity and strong connectivity infrastructure. Connectivity speeds in the city centre are internationally comparable, and broadband costs have steadily become cheaper as competition between fibre providers picks up.

This set of characteristics has contributed to historical and forecast growth for this sector that eclipses that for any other services sector in the Western Cape[4]. The strong technology sector presence in the greater Cape Town area has given rise to several initiatives to encourage collaboration and networking among market players. The most prominent of these are listed in Table 1.[5]

Table 1: Collaborative initiatives in the CTSDC

These initiatives either directly or indirectly promote the CTSDC through awareness-raising, business promotion, liaison with the local and provincial government, business incubation and intellectual property support. They reflect the collaborative aspect of Silicon Cape that is necessary to enable coordination of efforts to promote the sector.

The companies that dominate the Cape Town technology sector are made up of media focussed enterprises (Naspers), Amazon Web Services (web hosting), mobile payments (Fundamo, ACI, Entersekt and SnapScan), payments gateways (PayFast), web security (Thawte) and messaging (Clickatell). Excluding Naspers, which does not develop software, and with the exception of Thawte, all of these companies are regionally-based, in other words, they owe their existence to regional market specifics. The CTSDC has only spawned one internationally-relevant large business, Thawte, the brainchild of Cape Town tech entrepreneur Mark Shuttleworth. This does not mean that small businesses within the CTSDC are not internationally-focused. Companies such as Sudonem, FanCam and 4i Mobile have international investment and market connections. It is possible that the more dynamic and flexible nature of the smaller businesses lends itself better to international collaboration.

Links to manufacturing

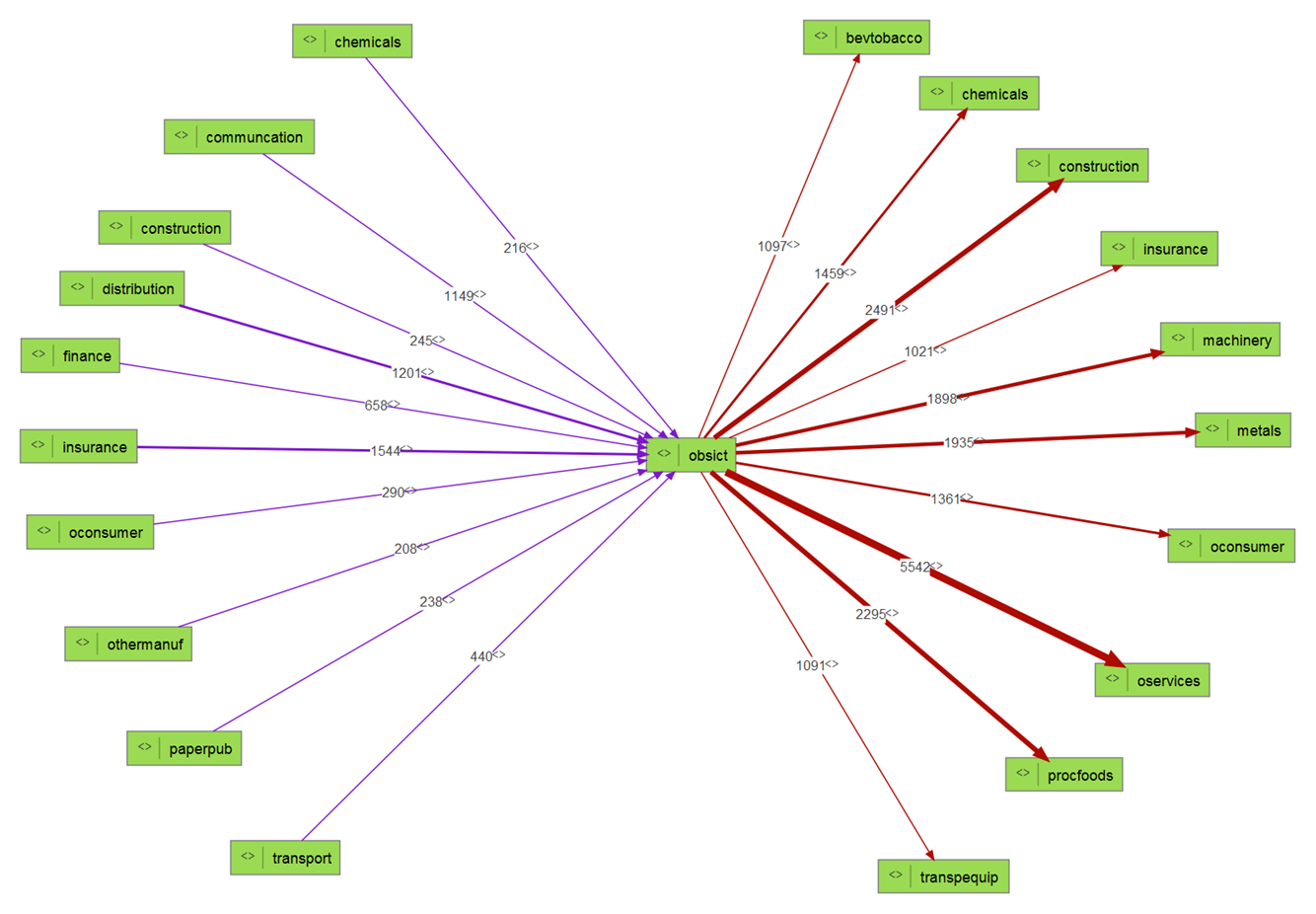

Links of the CTSDC to the manufacturing sector are present but not very significant. Some idea of the nature of the sector can be gained from observing the supply-use flows in Error! Reference source not found..[6]

This figure shows the top ten (by value) backward and forward linked sectors to the broadly-defined ICT sector in South Africa, for domestic production (GDP). It is clear the sector is more forward-linked than backward-linked, as services sectors usually are. The red arrows are forward links – in which value generated by the ICT sector is absorbed by downstream sectors – and the purple arrows are backward-linked sectors – which generate value that is absorbed by the ICT sector. The weights of the arrows (thickness) approximate the size of the flow of value.

More insight into these patterns can be gained from the information in TablesTable 2Table 3. They show that the most important value flows for the sector are intra-flows. Intra-sector flows represent 37% of forward-linked value flows and 68% of backward-linked flows. Furthermore, the second largest forward flow is also to a services sector. There are forward links to manufacturing sectors however, in processed foods (6%), machinery (5%), chemicals (4%), beverages and tobacco (3%) and transport equipment (3%). Forward links to other manufacturing sectors may be present but fall below the top 10 forward linked sectors.

In terms of backward linked sectors, the value added absorbed by the ICT sector is overwhelmingly based on services. However paper & publishing, chemicals and other manufacturing together make up 3% of the backward value absorbed by the ICT sector. It is important to bear in mind, however, that this data applies to the ICT sector as a whole, of which the CTSDC is but one component.

Figure 1: Top 10 forward and backward linked value flow sectors to 'other business services and ICT’

Table 2: Forward linked Value Added (VA)

Source: Constructed from data in World Bank. 2015. Export value-added database

Table 3: Backward linked VA

Source: Constructed from data in World Bank. 2015. Export value-added database

In general terms, the software industry is linked to manufacturing via the operating systems, database, back office and management information systems (MIS) that are utilised. However, no South African software company is a significant provider of these types of software, which are usually produced internationally by large multinationals exploiting economies of scale.

Many applications in the electronics manufacturing industry make use of embedded software, which is code specifically developed to control and run devices and machines. This code is usually written in a different language to that used for other types of software application such as business, web and mobile. However, this is an area where the sectors are linked and policies that promote one sector can be expected to have some impact on the other.

Servicification of manufacturing

The value added by software services to manufacturing is but one aspect of what is known as ‘the servicification of manufacturing’. This refers to the rising services content of manufacturing, whether as backward value-added, concomitantly in the production process or as part of the product package at the marketing stage and beyond. However, while services in general are estimated to account for around one third of value added to manufacturing sales and exports[7], the figure for software is but a fraction of this (as cited above).

Constraints and challenges faced by the sector

One of the most important constraints on the CTSDC is the access to finance. Respondents cited venture capitalists and financiers as the among the most important of the stakeholders in the industry.[8] The sector is quite dynamic, with a rapid rate of product redundancy and the existence of activity bubbles. This creates the need for flexible financing options, so that firms can adjust rapidly to changes in the environment. However the respondents complained that the ‘venture capitalists’ associated with the CTSDC do not function as true venture capitalists but instead look for safe bets and going concerns. This robs the industry of the angel investor presence required to seed innovation and fund risky but potentially high-return ventures. This point was re-iterated by interviews with software firms, including those based at the Launch Lab.[9] Start-ups go through a series of stages before becoming profitable. A commonly held view is that the first ‘innovation’ stage is very difficult to finance as venture capital only becomes available in the second ‘seed funding’ stage.

A second constraint relating to finance is the typical quantum of finance per project, which is seen as too small to seed a new business. Interviewees felt that in the US, funders were prepared to take bigger risks and far larger amounts of funding were available.

A third constraint is skills. Software developers and engineers are highly regarded but expensive with salaries being driven up by high demand.[10] Salaries are much lower in India and somewhat lower in eastern Europe. Respondents bemoaned the lack of entrepreneurial skills.

From interviews conducted, a serious problem appears to the application of intellectual property (IP) laws, which is encouraging firms to set up offshore companies, to house their IP.[11]

Various firms in the sector experience aspects of the regulatory environment as a constraint to business. Legislation such as the Protection of Information Act and and ICASA and FICA/FAIS regulations are seen by some as onerous and inhibiting to the market.

There are challenges accessing markets, in terms of direct marketing and the effectiveness of this as well as the existence of information asymmetries. The marketing environment is also continually evolving and traditional media is becoming less important, in favour of social media. This holds risks for South African businesses, which have to deal with international marketing platforms with rates denominated in dollars (or at least with partial exchange-rate pass through). Rand weakness then has the capacity to push marketing expenses over budget.

Some firms cited direct references and referrals as one of their most important ways of accessing new business, but digital platforms such as LinkedIn are included in this category.

There are also challenges in accessing coordination and collaboration with international market players. While it is undoubtedly advanced in many respects, the CTSDC’s remote location means that its role as a small satellite of the global sector cannot be upgraded without significant market penetration above the current level.

A related issue is that of integration into value chains, both global and regional, which is not significant. This could be a result of the sector being part of the ‘global south’ and economic aspects such as the volatile rand.

However, geographic remoteness from major global economic centres is not a major disadvantage in this sector and the widespread use of English is an advantage. Better integration into global value chains can assist with technology transfer, risk spreading and market expansion.

Such is the quality of the software skills available in the CTSDC, that multinationals such as Amazon are willing and able to pay dollar-parity salaries to their high skilled employees. This does, however, contribute to the bidding up of salaries for technical staff and reduces availability of these skills to the nascent start-up component. The availability and affordability of skills is therefore a constraint (especially to the small and micro component of the sector).

Foresight analysis and potential for disruption

The software industry is a driver of technological change, it does not respond in a reactive way to technological change, in the way that other sectors do. In other words, it is not subject to 'disruption' in the same way as, for example, the manufacturing sector is being disrupted by automation; or the aviation sector by drone technology. The source of disruption is a collection of revolutionary technologies known as the ‘new digital economy’ (NDE)[12], which is comprised of five pillar technologies:

Robotics and automation

New data sets drawn from mobile and computer devices, made possible by high connectivity speeds (broadband)

Cloud computing

Big data analytics – powerful algorithms to draw out patterns and meaning from large datasets

Artificial intelligence and machine learning

It is evident that the above pillars of the NDE all proceed from the software sector, in combination with rapidly advancing hardware complexity and capacity. Nevertheless, the sector that drives disruption can itself experience disruption. There is, in a sense, an ongoing disruptive momentum in the industry due to the rapid rate of innovation and corresponding redundancy. But market players are rarely ‘surprised’ by disruption, for example in the way the hotel industry was impacted by the Airbnb platform, or the taxi industry was impacted by the Uber platform. These traditional disruptions happened rapidly and caught the industry and regulators off guard, leading to typical symptoms of disruption - rapid reorganization of the industry with clear winners (consumers and disruptors) and losers (the ‘old technology’ suppliers). Such significant, discrete shifts in the fundamental modes of business are not evident in the software sector, but a form of underlying disruption may still take place as innovation in various areas overtakes older methods of doing things.

What then are the potential disrupting technologies that may impact the CTSDC over the next ten years? Firstly, cloud computing services are in the process of disrupting on-premise computing services.[13] With the pervasiveness in urban areas of wireless and fixed line broadband, internet access has never been better or cheaper. Firms no longer see benefit in buying and installing local copies of software such as management information systems, project management software, office software and backup & storage. It makes more sense to rent these systems as software as a service (SAAS) products, where a local copy is supplemented by an ever-updating system core that exists in the cloud.

Secondly, business to business (B2B) dealings in the software and data industry are undergoing some major changes and disruptions. Clients of these services typically allowed long service provision cycles and contract lives, allowing service providers to be locked in to a long contract cycle. This is now changing, with clients increasingly opting for shorter service provision cycles and looking for greater flexibility and agility from their service providers. This has increased competition in the B2B software and data service industry and placed the more slowly-adapting or less client aware firms under pressure.

The entire industry is currently dealing with the implications of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.[14] These technologies are becoming more and more accessible and easier to actuate in applications and software. Basically, AI and machine learning allow pattern recognition and solution finding to be partially automated and super-charged with the immense power of modern computing. Software design, process flow and testing & debugging can all be improved and accelerated with the application of these technologies.

An application of AI that is particularly relevant to knowledge-based sectors is augmented analytics (AA).[15] AA is the application of AI to large datasets to allow drilling into, visualization and sharing of relevant data. It will impact the data-orientated component of the industry.

Customer service methods are increasingly being augmented by chatbots – programmes that use artificial intelligence to create a customer interface robot that can chat to a customer via a messaging or chat application.[16] This serves to make the human customer interface less important and will make part of the human component of this sector redundant.

Finally, distributed ledger technologies (blockchain) have many applications, the most important probably being to the financial services sector. Proximate to this sector is the fintech (financial technology) sub sector of the software industry, which will also face disruption.[17] Blockchain creates a public, virtually-maintained record of transactions to promote transparency and eliminate opportunities for fraud and other criminal activities. Given that it has the potential to be the base on which a peer-to-peer (P2P) financial system could be built (leading to widespread financial disintermediation), its existence needs to be taken seriously by all players in the financial services sector, including the fintech component of the software industry.

Policy recommendations

In order to alleviate the supply of finance to the sector, which appears to be the primary constraint, foreign direct investment should be viewed as an option to supplement domestic finance. This could be part of a broader investment policy, but the needs of the CTSDC are specialised in that the sector is more innovative and cutting-edge than for example, the chemicals or plastics sectors. A specific programme for angel investment into the sector could be developed. Other mechanisms for small and micro enterprises (SMEs) include tax incentives, financing guarantee schemes and preferential procurement.

Secondly, efforts should be made to streamline regulations applicable to the sector, starting with the legislation cited earlier in this brief. Tariffs, surcharges and levies related to compliance should also be reviewed.

Rationalising of regulations is one aspect; the other is support to SMEs from local and provincial government towards compliance. The City of Cape Town has created a ‘red tape reduction unit’ with this specific purpose in mind. However, this unit’s scope should not be limited to assistance but it must be seen to have the credibility to revert to policy making bodies with recommendations to rationalise regulations.

Regarding market access, coordination and collaboration, there are already collaborative initiatives in place, as cited earlier in this brief. Given that SMEs continue to experience challenges in this area, these initiatives should look into extending their activities to better assist smaller businesses in the sector. This could include creating a portal that links market players and matches supply with demand. It could also serve as a price-setting mechanism and help align pricing with international norms.

The CTSDC has produced several success stories in the mobile payments arena – Fundamo and Entersekt are the two most prominent examples. Their services reside on mobile platforms but provide financial services and as such fall under financial regulation. In order for excessive regulatory compliance to not become a constraint on responsive development in the sector, harmonised and cross-silo policies need to be developed. This will become especially important as crypto-currencies and their associated payment technologies are increasingly used for transacting (currently these technologies do not have wide usage for transactional purposes).

In order to avoid experiencing disruption, the CTSDC needs to stay agile and aware of the major technological shifts listed in the foresight analysis section. The responsibility to remain current with technology primarily falls on the business, especially in the technology sector itself. However the collaborative initiatives, such as Silicon Cape, could assist in this by disseminating information and holding colloquiums and workshops to keep the local industry abreast of developments.

Finally, to reduce uncertainty and help smooth income and expenses for globally integrated businesses, stable exchange rates or rand weakness hedging facilities would be of assistance. Less rand volatility would also assist in attracting and retaining FDI.

This policy brief is part of a series developed for the Industrial Development Think Tank (IDTT).

You can find more information about the IDTT here.

You can download this policy brief here.

[1] Associate, tralac

[2] Professor, PRISM, School of Economics, University of Cape Town

[3] Statistics SA. 2017. Information and communication technology satellite account for SA 2013-14. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

[4] Western Cape Government. 2013. Provincial economic review and outlook. Western Cape Provincial Treasury: Cape Town

[5] Stuart, J. 2017. Value Chains in the Global South: Case Studies of the Cape Town ICT Sector. tralac Working Paper No. US17WP05/2017. Stellenbosch: tralac

[6] Stuart, J. 2017. Value Chains in the Global South: Case Studies of the Cape Town ICT Sector. tralac Working Paper No. US17WP05/2017. Stellenbosch: tralac

[7] Miroudot, S. and Cadestin, C., 2017. Services in global value chains: From inputs to value-creating activities (No. 197). OECD Publishing.

[8] These responses were part of a survey of Cape based ICT sector entrepreneurs that was reported on in Stuart (2017) (see reference above).

[9] Interviews conducted in October, 2018.

[10] Interviews, October 2018. Amazon’s Cape Town office is currently hiring a large number of staff at rates above the norm.

[11] See also ‘Software development sunk by IP laws’. https://www.itweb.co.za/content/DVgZeyvJ8YzMdjX9

[12] See UNCTAD. 2017. The new digital economy and development. Technical Note No.8 Unedited. Geneva: UNCTAD

[13] Armbrust, M., Fox, A., Griffith, R., Joseph, A.D., Katz, R., Konwinski, A., Lee, G., Patterson, D., Rabkin, A., Stoica, I. and Zaharia, M., 2010. A view of cloud computing. Communications of the ACM, 53(4), pp.50-58.

[14] Janakiram, M. 2018. How modern infrastructure and machine intelligence will disrupt the industry. Forbes Online at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/janakirammsv/2018/03/04/how-modern-infrastructure-and-machine-intelligence-will-disrupt-the-industry

[15] Martin, V. 2018. Augmented analytics: The future of business intelligence. Finextra Online at: https://www.finextra.com/blogposting/15195/augmented-analytics-the-future-of-business-intelligence

[16] Swanson, M. The 200 billion dollar chatbot disruption. Venture Beat online at: https://venturebeat.com/2016/05/01/the-200-billion-dollar-chatbot-disruption/

[17] Tech Racers, 2018. How is blockchain disrupting the fintech industry?. Online at https://www.techracers.com/blogs/blockchain-technology-in-fintech-industry/