Industrial Development Think Tank: Policy Brief 7[2]

Ndiadivha Tempia, Maria Nkhonjera, Reena das Nair and Shingie Chisoro

Structural transformation in agro-processing involves developing processing industries to transform raw agricultural inputs into high value-added products (known as sectoral transitioning) and upgrading of technology and productivity within agro-processing (sectoral deepening).[3] Developments in agro-processing industries and their dynamic linkages to other sectors of the economy, such as retail, logistics and packaging are a key source of technology-driven productivity growth and innovation, with direct implications for industrialisation.

Agro-processing value chains in South Africa remain concentrated, with limited participation of smaller processors of value added foods. The structural transformation of agro-processing value chains has been constrained not only by the the behaviour of incumbent firms, but also the legacy of historical policies which have served to maintain and protect high concentration levels.

By drawing on studies in the dairy and sugar value chains, this policy brief sheds light on some of the key obstacles and opportunities towards greater structural transformation in the agro-processing sector.

Exports of high value-added processed food products are an indication of the existence of capabilities.4 Changes in the production and trade of value-added products in the sugar and dairy sector illustrates the extent of growth and structural transformation in sugar and dairy value chains. Therefore, sustaining growth in exports of processed products requires firms to develop and upgrade their productive capabilities.

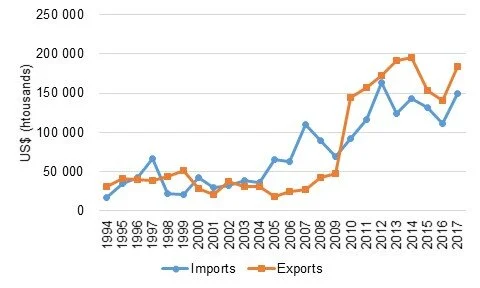

Structural transformation in the dairy sector entails a shift from milk processing, towards the production of high value-added concentrated dairy products such as cheese, butter, cream and yoghurt. South Africa was a net exporter of high value-added dairy products between 1994 and 2003, after which the country became a net importer up to 2015 (Figure 1).[4] The spike in exports in 2009 is explained by the inclusion in the trade data of South African exports to Southern African Customs Union (SACU) countries in the trade data, previously these were considered as domestic sales in the data. Since 2015, exports have recovered, but this has been matched by a high import penetration (largely from Europe). This suggests that imports are replacing the domestic production of processed dairy products.

Figure 1: Trade of processed dairy products

Source: Quantec data

Note: Processed dairy products include milk and cream (concentrated), buttermilk, whey butter, cheese and curd

The sugar sector also has strong linkages to downstream processing in sugar confectionery, beverages and food processing, where the most value is added. In the sugar industry, South Africa has mainly been a net importer of key sugar confectionery products (Figure 2) since 2002[5], suggesting that there has been limited value addition in the sector. More recently however, the country has recorded a positive trade balance (since 2011) in these product categories. Recent research shows that South Africa is seen as a gateway for exports into the southern African region which has subsequently encouraged greenfield investments and exports by medium-sized confectionery producers in the country. Important to note too, is that exports seen in Figure 1 and 2 are largely driven by demand in the region.

Figure 2: Trade of sugar confectionery products

Source: Quantec data

Note: sugar confectionery products include sweets, chocolates and baked goods (incl. biscuits).

Identifying constraints and opportunities for value addition

Entrants in both dairy and sugar value chains face barriers to entry/expansion as resulting from the conduct of the incumbent firms that strategically leverage their positions of market power to affect competitive outcomes at different levels of the value chain.

In the dairy sector, the market power of large multinationals (MNCs) who have buyer power over the price of raw milk from milk producers/farmers puts smaller processors at a competitive disadvantage. This makes it especially difficult for smaller processors to capture value at the primary processing level. Furthermore, there has been an increasing trend in mergers and acquisitions which involve MNCs buying out existing businesses in new or niche markets in the dairy sector. At least six mergers took place in the sector between 2011 and 2016, the majority of which involved Clover, the largest dairy processor in South Africa. These mergers and acquisitions are driven by global competition and concentration, with limited concern for domestic production and policy orientation towards inclusive growth for small-scale enterprises. Exports (Figure 1) are therefore largely driven by MNC’s such as Clover and Parmalat. Acquiring smaller milk processors removes effective rivalry, reduces inclusive participation and reinforces the concentrated nature of the market.

The sugar confectionary sector is similarly concentrated and dominated by MNCs such as Mondelez (Cadbury), Nestlé, Tiger Brands and Premier Foods. However, limited value-addition in the sugar sector, particularly by smaller and medium-sized players, is to a large extent explained by the current legislative framework that continues to protect sugar millers and sugarcane growers. These upstream levels of the value chain have benefitted from extensive state support and protection through the Sugar Act and Sugar Industry Agreement (SIA). These pieces of legislation provide the mechanism for setting the sugarcane price. A regulated cane price and well understood framework appears to inadvertently enable millers to collectively set the final selling price for sugar around a range. The industry is further protected through tariffs, which have been subject to heavy lobbying by the South African Sugar Association (SASA) - representing millers and growers. The effect of this protection is that input prices of sugar are high, making the sugar confectionery level of the value chain uncompetitive relative to imports.

There are however opportunities for adding value to both sugar and dairy products due to increasing consumer demand, rising disposable incomes and rapid urbanisation in the southern African region.

In dairy, the changing preferences and growing consumer demand for high-value dairy products (such as cheese, high quality butter and yoghurt at the secondary processing level), creates room for niche markets to be exploited. Significant financial resources are needed to enter the primary milk processing level, given extensive logistics infrastructure and integrated cold chain required. However, targeting niche products at the secondary level, where start-up costs are less restrictive and where it is cost-effective to operate at a small scale, offers a more sustainable and viable opportunity for value-addition by entrants, especially smaller players.

The South African sugar confectionery industry produces international brands, including high-value, niche product items destined for overseas markets. There are further indications that medium-sized firms have the capabilities to tap into regional markets, increasing exports and enhancing industrialisation.[6] For meaningful structural transformation and to spur further production and exports in the sugar sector, there is need to increase the competitiveness of downstream confectionery processers, rather than a historical focus of policy only on the upstream milling level.

Market access for small and medium processors

While upstream input costs are a major driver of competitiveness in downstream agro-processing value chains, access to markets is equally essential to grow and develop food processing firms. A large and growing proportion of processed food exports from South Africa goes into the SADC region. The expansion of South African retail chains into the region has stimulated this increase in exports and can be a useful catalyst to further spur industrialisation of food processors. Supermarket chains are a key channel for sugar confectionery and dairy products, and agro-food products more generally. The growing presence of large supermarkets has however created strong buyer-driven value chains with supermarkets wielding considerable buyer power. The main supermarket chains (Pick n Pay, Shoprite Checkers, The Spar Group and Woolworths Holdings) account for over 70% of formal retail chain market share nationally.[7]

Concerns around the abuse of buyer power and exertion of market power have a direct impact on suppliers of value-added food products.[8] Buyer power gives retailers the ability to extract margins at the expense of suppliers through trading terms. In the sugar sector, confectionery producers highlight that long payment periods, high listing/support fees, high till position payments and other requirements make penetrating the formal retail market difficult. Most dairy products are also distributed through supermarkets, who tend to negotiate prices on a national level. This puts retailers in a stronger bargaining position[9] relative to suppliers. In some cases, major retailers use their own wholesale companies and distribution centres to centrally source and internally distribute products from contracted farmers or suppliers.[10] The creation of vertically linked supply chains and increased use of contracts with major suppliers potentially excludes small and medium-sized enterprises in the food sector.[11] Smaller processors are therefore forced to compete with MNCs with well-known brands, in order to access supermarket shelf space and also meet the scale, quality standards and other requirements demanded by supermarkets. This comes at a cost and can potentially undermine inclusive growth and reduce the pace of structural transformation in the food sector if no supportive policies are put in place.

Policy agenda for creating and capturing value in agro-processing

The transformation process in South Africa’s agro-processing value chains (as shown in the case of sugar and dairy) has been limited and has not presented equal opportunities, particularly for entrants and smaller players. Supportive policies are therefore required to create and maintain a dynamic food processing industry.

The process of value addition in South Africa would require improved access to capital and processing technologies in order to support rivalry and increase participation of smaller processors. Investments in infrastructure such as storage, integrated cold chain (for dairy products) and extensive logistics are therefore key. Innovative packaging and new innovative products are also essential for the food industry. New product development activities would require a strong emphasis on R&D, which could include joint research facilities and testing centres for both large and small processing firms.

Downstream development further needs to be considered in the context of concentrated input markets and increasing concentration of large MNCs. This means that there needs to be continued and greater efforts to incorporate black industrialists and small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in general into agricultural value chains. This includes ensuring that these black industrialists can access competitively priced inputs and effectively compete and access markets. There is also a role for competition authorities and regulation in ensuring the market power of MNCs do not hinder the growth or in effect exclude entrants and therefore limit the growth prospects for processing and industrialisation.

In dairy, concerted efforts must be placed where maximum benefits can be achieved. This means providing further support to small-scale dairy processors producing value-added, niche products at the downstream level (where there has been some successful entry). Increased value-addition at this level could be supported in various ways, including through upgrading processing technologies, improving labelling and packaging equipment and processes, and assistance with marketing. This requires access to development finance, skills and relevant facilities.

In the sugar sector, the ongoing review of the Sugar Act and SIA should consider how the regulatory environment is affecting opportunities for downstream industrialisation.[12] Policy interventions must thus address the regulatory framework to achieve more competitive input sugar prices for downstream confectionery producers.

Government or private sector initiatives to develop capabilities and competitiveness in agro-processing are wasted if entrants are unable to get their products to final consumers. Supermarkets are a strong catalyst for stimulating food processing industries. A key area where concrete interventions can ease access to routes to market for food processors through supermarket chains is the development of focused supplier development programmes, and codes of conduct which guide the relationship between suppliers and supermarkets and limit the potential for abuses of buyer power by supermarket chains. The dti, through the 2017/18 Industrial Policy Action Plan (IPAP) has started considering these initiatives. This is important to develop supplier capabilities and ensure their sustainability.

The production of house brands or private label brands (that bear supermarket or no name branding) is also an opportunity to incorporate small and medium-sized confectionery and value-added dairy producers in supermarket chains. Given limited branding and advertising for these products, costs of sales are often lower than the equivalent well-known branded products. They also incur lower packaging and labelling costs, making it easier for entrants to competitively supply supermarkets. Suppliers can use this as a stepping stone to get onto supermarkets’ preferred supplier lists, with aims to supply export markets and upgrade capabilities over time.

Investments in purchasing of new monitoring systems, and access to testing stations are also essential for assisting smaller processors in adhering to quality standards required by supermarkets.

Importantly, value creation opportunities in the agro-food sector involve multiple stakeholders including government and the private sector (through farmers, processors, manufacturing firms, logistics services, retailers etc.). It is important therefore that initiatives encourage cooperation between these different participants in the value chain. In this regard, a multi-actor approach is necessary for black-industrialists and SMEs to become viable participants in the sector, with a high-level of coordination between various government departments.

This policy brief is part of a series developed for the Industrial Development Think Tank (IDTT).

You can find more information about the IDTT here.

You can download this policy brief here.

For more information regarding this brief contact the author (shingiec@uj.ac.za)

[1] This policy brief draws from the Industrial Development Think tank (IDTT) component study: Chisoro, S., das Nair, R., Nkhonjera, M. and Tempia, N. 2018. Structural transformation in agriculture and agro-processing.

[2] The Industrial Development Think Tank at UJ is housed in the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development, in conjunction with the SARChi Chair in Industrial Development, and supported by the DTI which is gratefully acknowledged. This paper reflects the views of the authors alone and not of the DTI or any other party.

[3] Andreoni, A. and Chang, H. 2016. Industrial Policy and the future of manufacturing. Economia e Politica Industriale. 43(4): 491-502

4 Ernst, Ganiastos, T. and Mytelka, L. (1998) Technological capabilities and Export Success in Asia. New York, Routledge.

[4] With exception of a short period between 2010 and 2011.

[5] If one considers key sugar containing products (sweets, chocolates and baked goods) collectively.

[6] das Nair, R. Nkhonjera, and Ziba, F., 2017. Growth and development in the sugar to confectionery value chain. Centre for Competition, Reguation and Economic Development, Working Paper 2016/17.

[7] das Nair and Chisoro, 2016.

[8] DAFF. 2014. A profile of the South Africa dairy market value chain.

[9] NAMC, 2003; das Nair and Chisoro, 2016; das Nair et al., 2017

[10] Weatherspoon and Reardon, 2003.

[11] Mather, C. 2005. SMEs in South Africa’s Food Processing Complex: Development Prospects, Constraints and Opportunities. Working Paper No.3.

[12] Findings should be understood within the context of growing health concerns and consumer demand for more nutritious, organic products which would require further capabilities in the production and export of such products.